Chapter 7: Conclusion

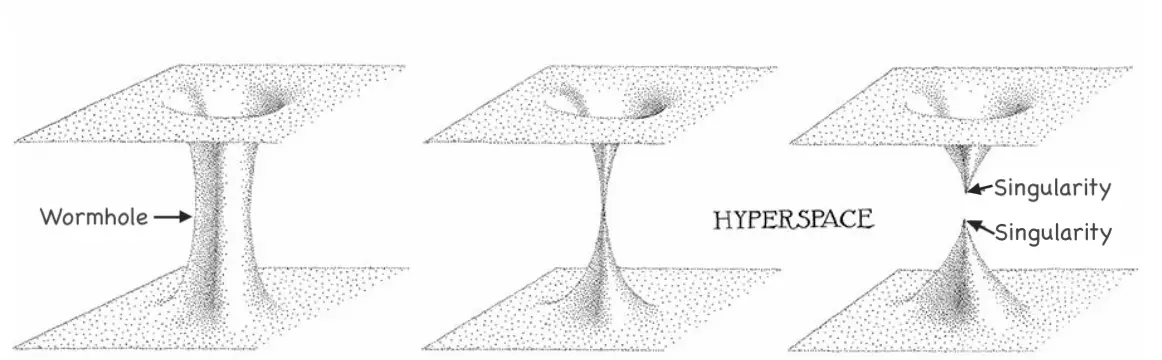

Wormholes have not been found naturally in our universe as they contradict the laws of physics. Black holes on the other hand, have been discovered existing in our universe, although they are many light-years away. Our models of these geometries are not accurate to that of the universe, firstly because our model is spherically symmetric and charge-less, which is unlikely to exist. Secondly, we have considered that the only light source present in both models is at an infinite distance away, which is unlikely the case. The surface and structure of the manifolds in these geometries in some cases can be similar to each other. Robert W. Fuller and John A. Wheeler, [15], discovered that a wormhole’s throat radius would shrink in size, until it is infinitesimally small, resulting in it pinching off so quickly that two singularities are formed, as seen in Figure 7.1, which has been taken from Figure 14.3 in Thornes’ book, [8]. The same was expected when two singularities in space collided with each other, causing the throat radius to grow and a wormhole to appear. This sequence of production, expansion, shrinkage and then pinching off happens so fast that nothing in our universe, including light, is fast enough to travel through it, as all geodesics are destroyed in the pinch off. For this reason, traversable wormholes, which do not pinch off, are used in our models. At the point when the wormhole pinches off, two embedded diagram with singularities have similar spacetime manifolds as two separate black holes. This work has been taken from Thornes’ book, [8].

In this report we discussed the basics of general relativity and the tensor calculus needed to discover that there exists a unique, distinct solution to the Einstein field equations, which numerically portrays the curvature of a spacetime’s manifold. The solution was derived for Schwarzschild black holes and for various types of wormhole geometries. These can be put together with the solutions of the geodesic equations to find systems of differential equations that encode the equations of motion of photons in each geometry. These were used to ray trace backwards in time to produce images of these black hole and wormholes.

The images produced of these two geometries had more similarities than differences. The first being that wormholes with large lensing widths distort the lower celestial sphere in the same way as Schwarzschild black holes, because the curvature of the wormholes can be made very similar to that of a black hole, as shown in Figure 7.1. This results in the primary and secondary images of the Milky Way appearing in the same way, due to the gravitational lensing occurring on structures of similar curvature. The presence of the Einstein ring in both images is produced by a caustic that is aligned with the camera, creating a perfect ring of light, near which stars behave in unusual ways. Minimal lensing takes place in wormholes with smaller lensing widths, hence the Milky Way galaxy on the exterior of the wormhole hardly changes in appearance. The main difference is observed in the centre of the images. In the black holes case, a black disc appears as all light-like geodesics are trapped in the non-escapable event horizon. This is due to the fact of black holes have singularities, whereas wormholes do not. In the wormholes case, a distortion of the upper celestial sphere is produced. The level of this distortion is directly linked to the parameter controlling the wormhole’s throat length. Increasing this length allows rays of light to travel along multiple paths from the upper celestial sphere, through the wormhole’s throat, to the camera, causing serval distorted images appearing in the wormhole’s interior.

Comparing the effective potential plots in both geometries, we see there is one unstable maximum potential in both plots, with no stable potentials. These unstable potentials are at the centre of the wormhole’s throat and on the photon sphere of the black hole. This is where photons orbit infinitely close towards these unstable areas. The slightest change of orbit would result in the photon’s potential tending towards zero as they travel to infinity. This is because at infinite distances away from their centres, the manifolds become flat, hence photons no longer feel the affect of the gravitational field produced by the black hole or the curvature of the wormhole. Photons with energies greater than this maximum potential can cross over this potential barrier. For black holes, this is crossing over the photon sphere, which leads to photons ending up inside the event horizon. For wormholes, this barrier is the throat, after which they escape to the other side of the wormhole.